Original research |

Peer reviewed |

A successful method of obtaining percutaneous liver biopsy samples of sufficient quantity for trace mineral analysis in adult swine without the aid of ultrasound

Un método eficiente para obtener muestras de biopsia percutánea de hígado en cantidades suficientes para analizar los minerales traza en cerdos adultos sin la ayuda del ultrasonido

Une méthode efficiente d'obtenir des échantillons de la biopsie du foie percutanée en la quantité suffisante pour l'analyse des minéraux trace dans lesanimaux adultes sans l'aide d'ultrason

Kevin E. Washburn, DVM, Diplomate ABVP, Diplomate ACVIM; Jeremy G. Powell, DVM; Charles V. Maxwell, PhD; Elizabeth B. Kegley, PhD; Zelpha Johnson, PhD; Timothy M. Fakler, PhD

KEW: Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma; JGP: University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas; CVM, EBK, ZJ: Department of Animal Science, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas; TMF: Zinpro Corporation, Eden Prairie, Minnesota; Corresponding author: Dr Kevin E. Washburn, Department of Veterinary Large Animal Clinical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Texas A&M University, 4475 TAMU, College Station, Texas 77843-4475

Cite as: Washburn KE, Powell JG, Maxwell CV, et al. A successful method of obtaining percutaneous liver biopsy samples of sufficient quantity for trace mineral analysis in adult swine without the aid of ultrasound. J Swine Health Prod. 2005;13(3):126-130.

Also available as a PDF.

SummaryObjectives: The objectives of this study were to determine if liver biopsy samples could be obtained percutaneously from large adult swine safely and in sufficient quantity to evaluate trace mineral status, and to determine if liver samples could be obtained without the aid of ultrasound. Materials and methods: Twelve healthy pigs with an average weight of 209 kg were randomly divided into two equal groups. The principal group of pigs were anesthetized and placed in left lateral recumbency. Percutaneous liver biopsies were performed, according to the expected anatomical location of the liver, for trace mineral analysis and histopathology. All principal pigs were necropsied 48 hours after the procedure and evaluated for significant lesions. Blood samples were obtained from all pigs, before anesthesia and 48 hours after the procedure, for hematology and serum chemical analysis. Results: Liver tissue was successfully obtained from all six principal pigs. An average of 440 mg of liver was obtained for trace mineral analysis. Hematology, serum chemical analysis, and necropsy results indicated no clinically significant complications as a result of the biopsy technique. Discussion: It appears that obtaining percutaneous liver biopsies of sufficient quantity for trace mineral analysis can be performed safely in adult pigs without the aid of ultrasound. This procedure may circumvent the need to obtain liver tissue via necropsy or laparotomy. Implications: Use of this percutaneous biopsy technique provides sufficient tissue for researchers to evaluate the trace mineral reservoir status of adult swine without requiring necropsy or laparotomy. | ResumenObjetivos: Los objetivos de este estudio fueron determinar si las muestras de una biopsia de hígado podían obtenerse percutáneamente de cerdos adultos sin riesgo y en cantidad suficiente para evaluar el nivel de los minerales traza, y determinar si las muestras de hígado podrían obtenerse sin la ayuda del ultrasonido. Materiales y métodos: Doce cerdos sanos con un peso promedio de 209 kg. fueron divididos al azar en dos grupos similares. Los cerdos del grupo principal fueron anestesiados y colocados en decúbito lateral izquierdo. Se efectuaron biopsias percutáneas de hígado, de acuerdo a la posición anatómica recomendada para un análisis de minerales traza e histopatología. Se efectuó la necropsia a todos los cerdos del grupo principal 48 horas después del procedimiento y se buscaron lesiones significativas. También se obtuvieron muestras de sangre de todos los cerdos, antes de la anestesia y 48 horas después del procedimiento para hematología y el análisis químico del suero. Resultados: El tejido del hígado se obtuvo exitosamente de los seis cerdos del grupo principal. Se obtuvo un promedio de 440 mg de hígado para análisis de minerales traza. La hematología, el análisis químico de suero y los resultados de la necropsia indicaron que no hubo complicaciones clínicamente significativas como resultado de la técnica de toma de la biopsia. Discusión: De acuerdo a los resultados, la toma de biopsias percutáneas de hígado en cantidades suficiente para analizar minerales traza puede efectuarse sin riesgo en cerdos adultos y sin la ayuda del ultrasonido. Este procedimiento puede evitar la necesidad de obtener tejido del hígado vía necropsia o laparotomía. Implicaciones: El uso de esta técnica puede permitir a los investigadores evaluar con más exactitud el estado de las reservas de minerales traza de los cerdos en todas las fases de la producción. | ResuméObjectifs: Les objectifs de cette étude ont été déterminer si les échantillons de la biopsie du foie puissent être obtenus percutaneously de les animaux adultes sans risque et dans la quantité suffisante pour évaluer le statut de les minéraux trace, et déterminer si les échantillons du foie puissent être obtenus sans l'aide d'ultrason. Matières et méthodes: Douze cochons sains avec un poids moyen de 209 kg ont été divisés au hasard en deux groupes égaux. Le groupe principal a été anesthésié et a été placé dans recumbency latéral gauche. Les biopsies du foie percutanées ont été exécutées selon l'emplacement anatomique attendu du foie, pour l'analyse des minéraux trace et de l'histopathology. Tous les animaux du groupe principal ont été necropsied 48 heures après la procédure et ont été évalué pour des lésions considérables. Les échantillons du sang ont été obtenus de tous les animaux, avant l'anesthésie et 48 heures après la procédure, pour l'analyse chimique du sérum et l'hématologie. Résultats: Le tissu du foie a été obtenu avec succès des six cochons du groupe principaux. Une moyenne de 440 mg de foie a été obtenue pour l'analyse des minéraux trace. L'hématologie, l'analyse chimique du sérum, et les résultats du necropsy ont indiqué qu'il n'y a pas de complications d'une manière clinique considérable à la suite de la technique de la biopsie. Discussion: Il paraît qu'obtenir des biopsies du foie percutanées dans la quantité suffisante pour l'analyse des minéraux trace peut être exécuté sans risque dans les cochons adultes sans l'aide d'ultrason. Cette procédure peut circonvenir le besoin d'obtenir le tissu du foie par la necropsy ou la laparotomy. Implications: L'usage de cette technique peut permettre aux chercheurs d'évaluer plus exactement le statut de la réserve des minéraux trace du animaux dans toutes les phases de la production. |

Keywords: swine, liver,

biopsy, needle

Search the AASV web site

for pages with similar keywords.

Received: June

2, 2004

Accepted: August

18, 2004

The balance and availability of trace minerals in feeds for swine have documented effects on various parameters of reproductive efficiency and performance.1,2 Body stores (ie, reservoirs) of these elements may be mobilized for use in times of demand. The liver serves as one such reservoir for many minerals, including copper and zinc, which play vital roles in ensuring optimal reproductive performance.3 Reservoir levels of trace minerals fluctuate as sows go through various phases of the production cycle, such as gestation, farrowing, and breeding.3 Inefficiencies in reproductive performance may occur if reservoir levels become depleted and are not adequately restored by dietary or supplemental means.3 The ability to assess available levels of minerals in reservoirs such as the liver, in pigs representing all phases of swine production, facilitates correction of deficiencies or imbalances and allows the efficacy of various mineral sources in the breeding herd to be evaluated. It has been reported that liver tissue for antemortem trace mineral analysis has been obtained via laparotomy4 and percutaneous biopsy.5-7 Performing a laparotomy in a field setting would be problematic due to the necessity of a sterile environment and inhalant anesthesia. In addition, a laparotomy on an adult pig would be labor intensive and time consuming. Percutaneous sampling has been performed using relatively small-diameter instruments and either a ventral paramedian,5 ventral midline,6 or right lateral approach through the tenth or eleventh intercostal space.7 A right lateral subcostal approach has been used; however, the procedure was performed in young pigs (20 to 30 kg body weight) using ultrasound guidance and was not described in detail.8 Detailed reports could not be found describing a successful percutaneous approach in pigs greater than 70 kg with or without the use of ultrasound guidance. In order to obtain liver tissue from adult sows, the described ventral paramedian or ventral midline approaches would be hindered by developed mammary tissue. Due to the location of the pleural attachment of the diaphragm, a right lateral approach through the tenth or eleventh intercostal space may result in inadvertent puncture of the thoracic cavity.5 According to anatomy texts and sketches, there is a "window" of percutaneously accessible liver on the right side of the pig, just ventral to the rib cage at approximately the level of the tenth rib.9 The authors conducted preliminary trials using five pigs, similar in size to adult sows, prior to beginning this study, to assess the viability of using a percutaneous approach in this location.

Ultrasound imaging equipment is cumbersome and expensive. In the field setting of a production unit, it would be of benefit to be able to consistently and safely obtain liver tissue without the use of ultrasound guidance.

Percutaneous biopsy of the porcine liver to obtain quantities of tissue sufficient for mineral analysis is inherently difficult due to the fibrous nature of the porcine liver, which contains more connective tissue than the bovine liver.9 Reports of using a large-bore instrument (ie, 6 mm outer diameter, 5 mm inside diameter) to obtain such samples could not be found.

The objective of this study was to determine if liver biopsy samples of sufficient quantity for trace mineral analysis could be safely obtained percutaneously from adult swine without the aid of ultrasound guidance and using a large-diameter instrument.

Materials and methods

Animals

Twelve healthy female pigs were randomly divided into two groups of six. The principal group consisted of one gilt, two first-parity sows, one second-parity sow, one third-parity sow, and one fourth-parity sow. The average weight of pigs in the principal group was 215 kg (range 166 kg to 259 kg). The control group consisted of one gilt, three first-parity sows, and two third-parity sows. The average weight of pigs in the control group was 202.5 kg (range 182.7 kg to 240 kg). All pigs were housed individually and cared for in compliance with Animal Care Protocol #04004 for swine experimentation issued by the University of Arkansas Animal Care Committee.

Anesthetic protocol

All pigs were anesthetized by intramuscular injection of 1 mL per 45.4 kg body weight of a mixture containing xylazine (5.5 mg per kg), ketamine (5.5 mg per kg), tiletamine (0.22 mg per kg), and zolazepam (0.22 mg per kg). This was compounded by using 2.5 mL xylazine (containing 100 mg per mL solution) and 2.5 mL ketamine (containing 100 mg per mL solution) to reconstitute powdered Telazol (tiletamine, 50 mg, and zolazepam, 50 mg; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, Iowa). A solution of 2% lidocaine hydrochloride (1 mL) was infiltrated in the skin at the site of liver biopsy.

Experimental design

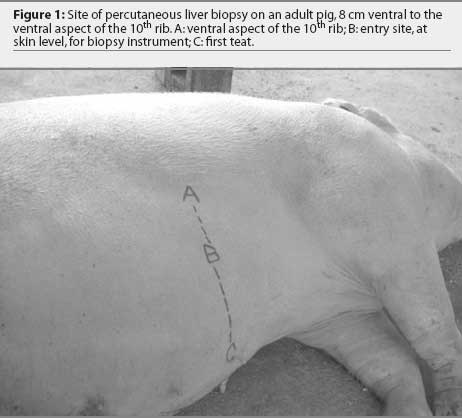

All pigs were weighed, had venous blood samples obtained via the jugular vein, were injected intramuscularly with the anesthetic agent, and were placed in left lateral recumbency. The location for liver biopsy was 8 cm (approximately one hand width) ventral to the rib cage on the right side at the level of the tenth rib (Figure 1). In five of the six pigs, this site also was consistently 16 cm (approximately two hand widths) dorsal to the first teat. For the remaining pig, this site was 16 cm dorsal to a point half way between the first and second teat.

The site for liver biopsy was clipped, infiltrated with lidocaine, and surgically prepared with 2% chlorhexidine scrub. A stab incision was made through the skin at the site of lidocaine infiltration with a #15 scalpel blade. In the control group, this stab incision was subsequently closed with one cruciate suture of 1-0 synthetic, non-absorbable suture (Braunamid; Jorgensen Laboratories Inc, Loveland, Colorado), and no liver biopsy was performed. In the principal group, liver biopsy was performed, and the skin incision was closed in the same manner as the control pigs. Blood samples were collected from all 12 pigs 48 hours after the biopsy procedure, and the six pigs of the principal group were euthanized by captive bolt pistol and exsanguinated. These pigs were necropsied and examined for significant lesions and location of the biopsy site. During the 2-day study, all pigs were observed by the investigators for changes in appetite and behavior and other indications of decline in general health.

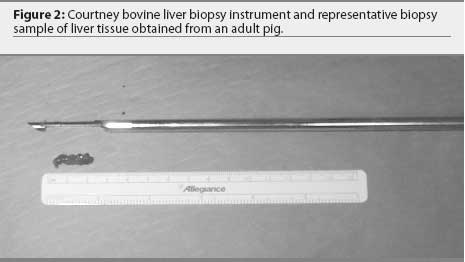

Liver biopsy

To confirm access to the liver from this site via histopathology, a biopsy sample was taken using a 14-gauge, Tru-cut biopsy instrument (Allegiance Healthcare Corporation, McGraw Park, Illinois) by passing the instrument through the stab incision to a depth of 8 cm. For mineral analysis, the liver was biopsied using a Courtney bovine liver biopsy instrument (Sontec Instruments Inc, Englewood, Colorado). The instrument is 32 cm long with the biopsy chamber fully extended, and has an outside diameter of 6 mm and an inside diameter of 5 mm. The tip is identical in construction to a Tru-cut biopsy instrument. The biopsy chamber is 3 cm long and 5 mm in diameter (Figure 2). The instrument was passed through the skin incision to a depth of 8 cm with the biopsy chamber in the fully retracted position. Proper depth of insertion was based on results of pilot trials using ultrasound to measure from the skin surface to the liver in pigs of similar size. At this point, the biopsy chamber was extended into the liver tissue. While holding the chamber stationary, the outside portion of the instrument was briskly moved over the chamber to excise a core of liver tissue. The entire instrument was removed, and the chamber was extended to reveal the removed tissue (Figure 2). The liver tissue was placed on an electronic scale and its mass recorded (Denver Instrument, Arvada, Colorado).

Sample analysis

Blood samples taken from all 12 pigs prior to anesthesia and 48 hours after the procedure were submitted to the Arkansas Livestock and Poultry Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (ALPVDL, Fayetteville, Arkansas) for hematology and serum chemical analysis. Primary parameters of interest included packed cell volume (PCV), total protein (TP), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase (ALK), and aspartase aminotransferase (AST). The tissue obtained from the 14-gauge Tru-cut biopsy instrument was placed in 10% formalin and submitted for histopathology (ALPVDL). The tissue obtained for mineral analysis with the Courtney bovine liver biopsy instrument was placed in plastic snap-cap tubes and frozen at -20 degrees C for future mineral analysis (ALPVDL).

Liver mineral concentrations were determined after drying and wet ashing the biopsy samples. Samples were thawed, transferred to 50-mL polypropylene tubes, and dried for 48 hours in a gravity convection oven at 100°C. Dry sample weights were obtained. Samples were digested in 15 mL of trace-metal-grade nitric acid at 115°C for 1 hour in the polypropylene tubes, then brought to a constant volume of 30 mL with deionized water and analyzed by atomic emission spectroscopy (Spectro ICP, Model FSMEA85D; Spectro Analytical Instruments Inc, Fitchburg, Massachusetts).

Postmortem evaluation

On postmortem examination, the abdominal cavity was examined for evidence of hemorrhage, gross contamination of the abdominal cavity, and accidental puncture of other organs. The entire liver was removed, and the exact site of liver puncture was recorded.

Data analysis

Results of hematology and chemical analysis for principal and control pigs were compared and analyzed for samples collected prior to anesthesia and liver biopsies and 48 hours after the procedure, using the mixed procedure of SAS (SAS/STAT, Version 8, 1999; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina). Hematology data were analyzed as a repeated measure with biopsy as the main effect and time as the repeated measure. Differences in measured parameters between principal and control pigs were considered significant at P < .05. Results of trace mineral levels obtained were not analyzed statistically.

Results

Following anesthetic administration, all pigs became laterally recumbent within 15 minutes and remained in the desirable plane of anesthesia for approximately 30 minutes. No adverse reactions to the anesthetic agents were noted during or following the procedure. Histopathology of the samples taken with the Tru-cut biopsy instrument to ensure proper location revealed liver tissue in all six principal pigs. Due to the nature of the porcine liver, an average of two samples using the Courtney bovine liver biopsy instrument were required to obtain sufficient tissue for mineral analysis. The average amount of liver obtained by combining the two samples was 440 mg (range 418 to 486 mg of wet tissue).

Clinically, all 12 pigs were in good health for the duration of the 48-hour study period. No significant differences in PCV, GGT, ALK, or AST were noted between principal and control groups prior to or 48 hours after the procedure. The PCV was within the reference range prior to and after the procedure in all but one pig; however, in that pig, PCV was abnormal prior to biopsy and normal 48 hours after the procedure. Serum GGT, ALK, and AST, obtained to assess liver damage as a result of the biopsy, displayed minor fluctuations from baseline values; however, none of the differences between the obtained values and baseline values were significant, nor were differences between principal and control pigs statistically significant. One pig had a significantly elevated GGT level prior to the procedure; however, GGT declined to normal reference range during the 48-hour period after the liver biopsy.

Pre-biopsy TP values in principal pigs were significantly lower than those of the control pigs (P = .04). However, there was no significant difference between TP values in principal and control pigs in samples obtained 48 hours after the procedure. Results of trace mineral analysis for liver biopsy samples are shown in Table 1 along with a normal reference range.

On gross postmortem examination, there was no evidence of gross abdominal hemorrhage, and no evidence that organs adjacent to the liver were inadvertently punctured or damaged. The size of the livers was consistent among pigs, with the exception of pig #223, which had a larger (nonpathologic) liver. The puncture sites in five of the six pigs were in the ventral one-third of the right medial liver lobe. In pig #223, the liver biopsy sites were in the left medial lobe. In two of the six pigs, a small volume of clotted blood (approximately 40 to 60 mL) was present surrounding the biopsy sites. The average distance from the skin surface to the liver surface was 7.0 cm.

Discussion

Results of our study suggest that a large-bore instrument capable of obtaining sufficient quantities of liver tissue for mineral analysis can be used percutaneously, without ultrasound guidance, in large adult swine. None of the pigs in this study sustained sufficient blood loss to appear abnormal clinically. Although TP values for principal pigs were significantly lower than for control pigs, this difference was noted prior to liver biopsy. In addition, all TP values from both control and principal pigs 48 hours after the procedure were within or above the normal reference range. Therefore, TP and PCV values suggested minimal hemorrhage as a result of percutaneous liver biopsy with a large-bore instrument.

It was not the intent of this study to interpret the mineral level status in these pigs, but rather to determine the feasibility of obtaining sufficient tissue to do so. We did not attempt to elucidate potential causes of discrepancies between values obtained and the normal ranges. However, a reference range is reported in order to evaluate grossly whether or not reasonably comparable results are obtained when liver tissue is obtained using our percutaneous technique, surgically, or at necropsy. In the opinion of the authors, trace mineral values were reasonably representative of the references ranges. The reasons phosphorus levels were markedly below and iron levels were markedly above the normal ranges were undetermined.

The pigs in this experiment were not fasted prior to anesthesia. In a field setting within a large production unit, fasting animals for the appropriate time prior to anesthesia may be impractical. The authors elected to perform the procedure as would likely be done in the field. Therefore, it was surmised that the risk of aspiration of regurgitated stomach contents during a relatively short procedure was minimal. In addition, in previous trials performed by the authors in pigs of similar size that were fasted 24 hours prior to anesthesia, the gall bladder, observed via ultrasound, was greatly enlarged. The risk of accidental puncture of a distended gall bladder was deemed to be greater than the risk of anesthetic complications. Consideration was given to the possibility that pigs might have eaten just prior to the experiment, thereby creating a distended stomach. However, the liver somewhat "protects" the stomach on the right side of the pig at the site where the biopsy was attempted. Therefore, unless the biopsy instrument were to be placed to a much greater depth than required to obtain liver tissue, the stomach was likely to be safe from inadvertent puncture. On necropsy, neither the gall bladder nor the stomach appeared to sustain injury by the procedure.

On postmortem examination, it was apparent that the biopsy sites were consistently within the right lobes of the liver (five of six). In the fourth-parity sow (#223), with the biopsy site located in the left medial liver lobe, the grossly enlarged nature of the liver appeared to have caused the left medial lobe to be ventral to the stomach, encroaching on the right side of the pig. In this instance, the stomach remained well protected from inadvertent puncture.

The liver tissue obtained via the Courtney bovine liver biopsy instrument appeared grossly as gelatinous, dark purple tissue. The same color and consistency was noted in samples obtained from cadaver porcine livers using the same Courtney bovine biopsy instrument in previous trials by the authors. Because of the fibrous nature of the porcine liver, there are inherent difficulties with obtaining substantial quantities of liver tissue percutaneously. We suspect that the connective tissue present in the porcine liver is largely "pushed" rather than punctured by the large-bore tip of the instrument, and that the integrity of the tissue adjacent to the tract created by the instrument is maintained such that a "core" of liver tissue less readily falls into the biopsy chamber for excision and removal.

Although it is certainly possible that this technique may not be useful for all sizes and sexes of swine, according to anatomical texts, this "window" of percutaneously accessible liver is consistently present. However, it is recommended that trials using ultrasound recognition and exact location of the liver be conducted prior to percutaneous biopsy in pigs smaller than the animals recorded here. Pregnant sows should be examined via ultrasound prior to performing this "blind" technique. The authors suspect that the location of the right lobe of the liver would prevent the gravid uterus from encroaching on the biopsy site.

Overall, although the numbers in this study were small, it appears that this procedure can be performed in a field setting with minimal hazard to the pigs. However, this procedure does require some practice and is not without some degree of risk. Avoiding laparotomy or postmortem sampling of pigs of this size to obtain trace mineral status would be beneficial in order to correct imbalances or deficiencies or to determine efficacy of a specific mineral source.

Implications

- Liver biopsies can be obtained percutaneously from large adult swine with a large-bore instrument in a practical field setting without the aid of ultrasound guidance.

- A significant amount of liver tissue can be obtained safely in order to measure such parameters as trace mineral levels.

- The procedure would circumvent the need to obtain liver tissue from large pigs via necropsy or laparotomy.

Acknowledgement

This project was funded by Zinpro Corporation, Eden Prairie, Minnesota.

References

1. Mahan DC, Penhale LH, Cline JH, Moxon AL, Fetter AW, Yarrington JT. Efficacy of supplemental selenium in reproductive diets on sow and progeny performance. J Anim Sci. 1974;39:536-543.

2. Wilkinson JE, Bell MC, Bacon JA, Masincupp FB. Effects of supplemental selenium on swine. I. Gestation and lactation. J Anim Sci. 1977;44:224-228.

3. Mahan DC. Mineral nutrition of the sow: A review. J Anim Sci. 1990;68:573-582.

4. Jensen M, Lindholm A, Hakkarainen J. The vitamin E distribution in serum, liver, adipose and muscle tissues in the pig during depletion and repletion. Acta Vet Scand. 1990;31:129-136.

5. Simmons F. Percutaneous hepatic biopsy technique for miniature swine. Am J Vet Res. 1971;32:491-493.

6. van Lith PM, Niewold TA, Vandenbooren CJMA, Verheijden JHM, Gruys E, Vernooy JCM, Kuypers AH. A longitudinal study of starvation in piglets and the introduction of a modified liver biopsy technique. Vet Q. 1988;10:145-150.

7. Swindle MM. Basic Surgical Exercises Using Swine. Philadelphia: Praeger Press; 1983.

8. Chow PK, Jeyaraj P, Tan SY, Cheong SF, Soo KC. Serial ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy in a partial hepatectomy porcine model: a new technique in the study of liver regeneration. J Surg Res. 1997;70:134-137.

9. Dyce KM, Sack WO, Wensing CJG. The abdomen of the pig. In: Pedersen D, ed. Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: WB Saunders Co; 1987:746-758.

10. Puls R. Mineral Levels in Animal Health: Diagnostic Data. 2nd ed. Clearbrook, British Columbia, Canada: Sherpa International; 1994